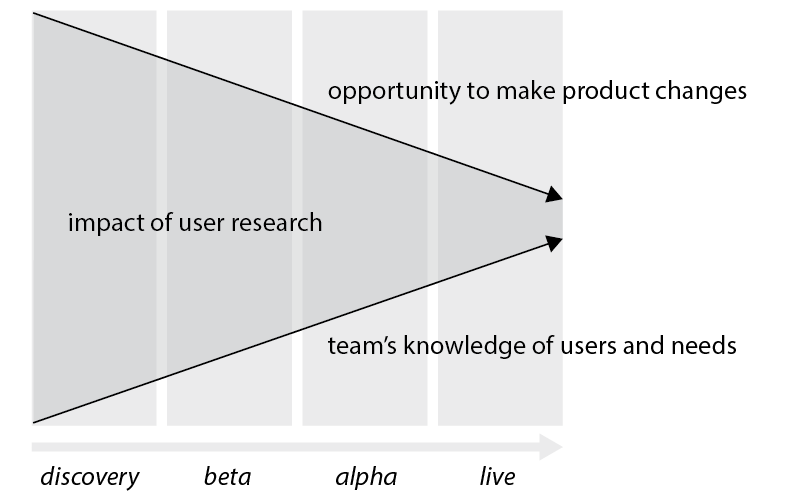

A user researcher’s influence diminishes as a product develops. That’s not meant as a clickbait-y controversial statement about the obsolescence of researchers. I mean: in an ideal world, their impact decreases – relatively – during the product lifecycle.

There are two key reasons for this.

Reason 1: the team gains more understanding of users

If a user researcher is embedded in a team, or acts as a consultant to a team, they are ideally involved at the start of a project. Early on they do exploratory research and over time they refine their approach and their questions. During these phases, the team they are working with will learn about the users and their needs through the research findings (again: ideally). As a result, the team’s understanding will increase, enabling them to apply that knowledge in the product’s development. This shared knowledge means the researcher is not alone in “advocating for the users”, and as such they become less vital in the team’s aim to deliver a user-centred product.

Reason 2: the product development reaches maturity

As the product development progresses, the scope narrows: open-ended questions are transforming into increasingly specific and detailed questions. Through prototyping and usability testing the team has learnt where and how the product meets users’ needs. This clarity and understanding means there should no longer be radically different insights from research. Research findings become less surprising, and significant changes are now costly and shouldn’t be needed (again: ideally).

So, to crudely summarise this in a more visual way:

Note that the impact of user research does not disappear: there is a wealth of things to learn from a live service through a wide variety of methods and sources: user feedback, analytics, usability testing, surveys, A/B testing, etc. The findings from live research may eventually also result in a new discovery, as users, products, and the context will likely change.

The purpose of user research during product development is to reduce uncertainty when it comes to making decisions. As Douglas Hubbard explains in ‘How to Measure Anything’, there is typically a high cost to being wrong, and research can help reduce this risk. While Hubbard focuses solely on quantitative measurements, some aspects relate to qualitative research too:

The information value curve is usually steepest at the beginning. The first 100 samples reduce uncertainty much more than the second 100. In fact, even the first 10 samples tell you a lot more than the next 10. The initial state of uncertainty tells you a lot about how to measure it. Remember, the more uncertainty you started out with, the more the initial observations will tell you. When starting from a position of extremely high uncertainty, even methods with a lot of inherent error can give you more information than you had before.

Hubbard, D. W. (2014). How to measure anything: Finding the value of intangibles in business. John Wiley & Sons.

In other words, research enables you to learn a lot in a short period of time, but there is a long tail of insights that require a more sustained and costly effort to uncover. The value of doing this work depends on many factors. Most importantly, it depends on the opportunity for research findings to affect change.

Personally, I’ve spent time working on live services that ultimately were unchangeable – regardless of what research may have uncovered. Reasons varied: monetary, legal, political, etc. As Hubbard puts it:

It is only important to measure if knowledge of the value could cause us to take different actions

For user researchers to be effective, advocating for when not to do research may be just as important as the reverse.