On 10 October 2022 I gave a Pecha Kucha presentation at the Ethnographic Praxis in Industry Conference (EPIC) about messy user journeys. Pecha Kuchas have a 20×20 format: 20 slides with 20 seconds of text. Below the transcript of this talk.

I would like to start with a quote.

“Publishing is basically my job. I share my research […] so others don’t have to start from scratch”, one author told me.

I study those who study. I do research on people who do research. Specifically: people who publish their work in academic journals.

As many of you will know, academic publishing involves the completion of a series of steps: completing some research, writing a manuscript, selecting a journal, meeting the journal requirements, submitting, going through a review process, making changes, and so forth.

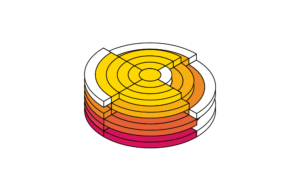

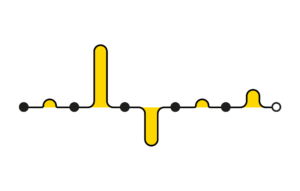

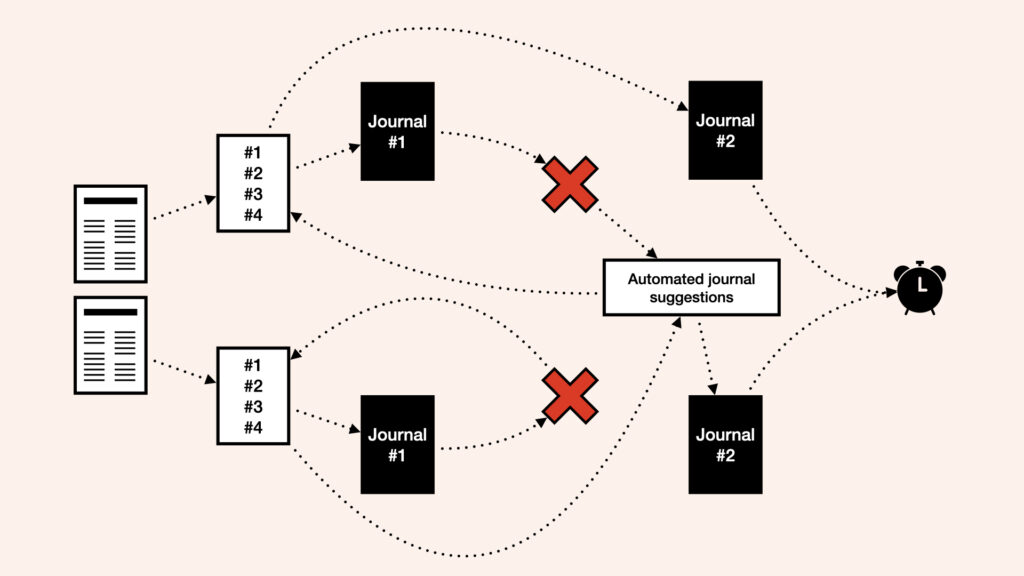

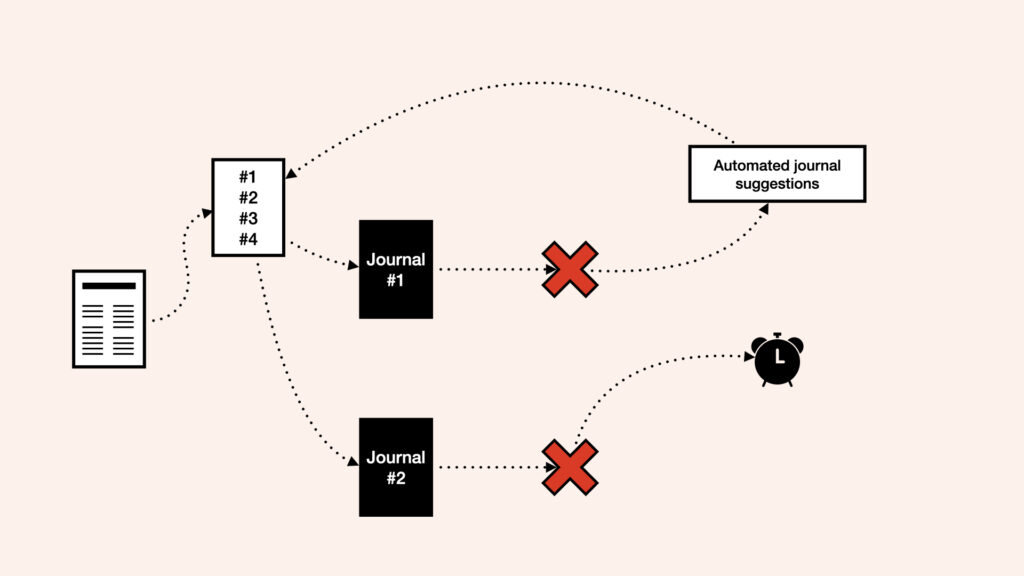

These steps are often depicted using diagrams like these, showing clean and unambiguous notations. They provide an illusion of certainty and linearity, even though this is often an unachievable ideal. They show actions in staccato.

Staccato, the musical notation for short separated tones, Italian for detached. The placement of the notes on the stave of staff means they are played in sequential order until – eventually – the piece is finished. This organised notation is of course a pragmatic way of viewing processes and systems. It doesn’t, however, convey the lived experience of publishing.

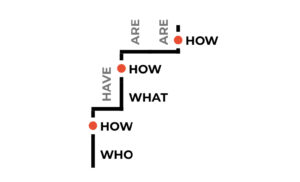

In fact, when I interview authors, they share stories that are anything but linear. Instead, the process is littered with iterations, revealed by terminology such as rewrite, revise, resubmit.

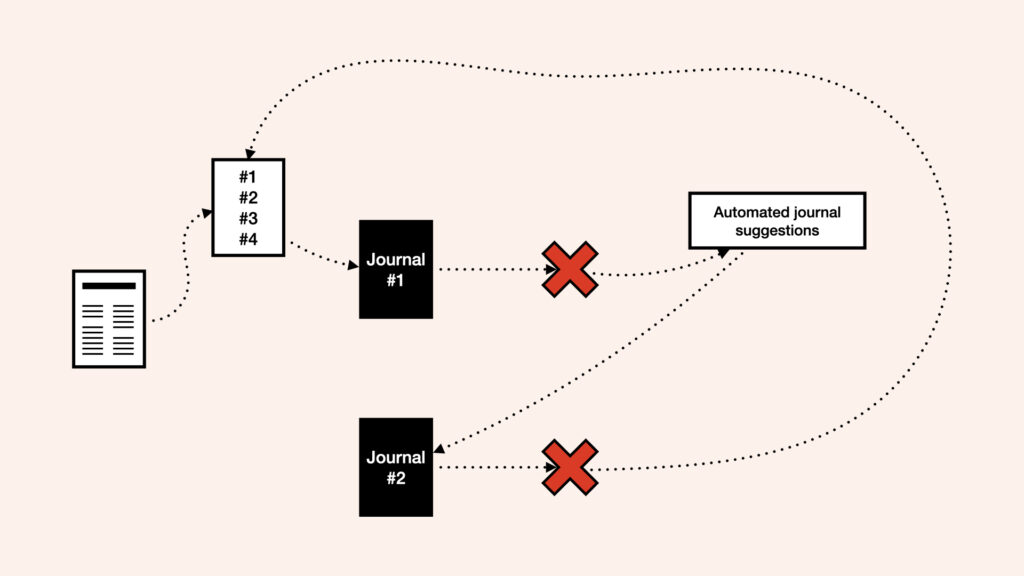

The concept of rejection is the main source of these iterations.

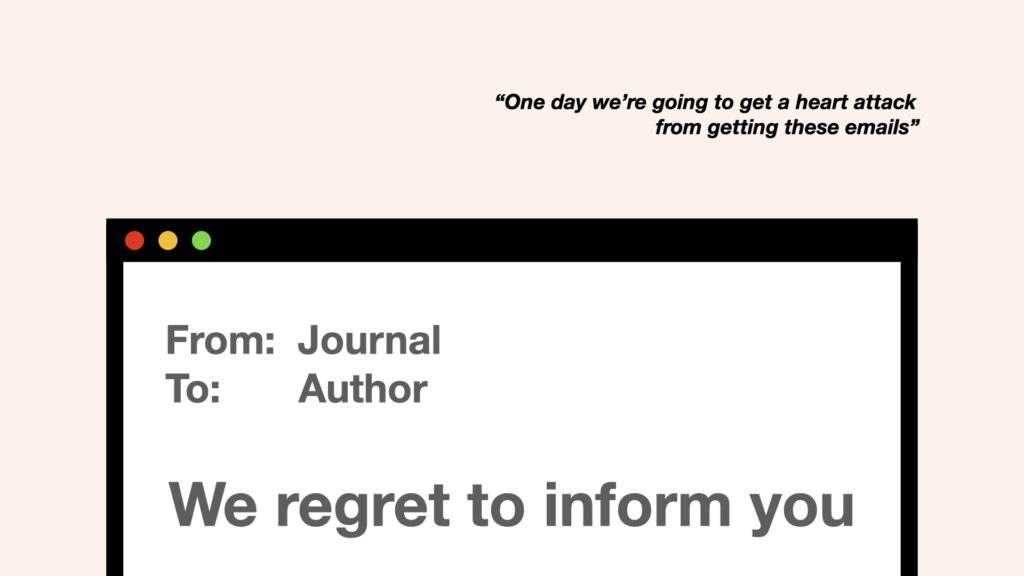

“We regret to inform you”, says every email delivering bad news to an author. Their work will not be published in this journal this time around. “One day we’re going to get a heart attack from getting these emails”, said one author to me – laughing.

Over the last year, I have been studying the experience of having your work be rejected. Given that many journals reject the vast majority of the manuscripts they receive, this is a commonplace occurrence.

Nevertheless, for many authors it can be an emotionally charged event. As one author said: “I was so upset […] It was quite a sad experience”. Sometimes people early in their career explain they cannot bear to read the reviews of their work immediately, instead they let them sit in their inbox for a few days until they can pluck up the courage.

But authors also acknowledge that rejection, feedback, and iterations are in many ways at the core of scientific progress. They present an opportunity to become better, as one author said: “My paper will improve if I pay attention to the comments.”

As authors progress in their career, they develop resilience to deal with this process. They create tools to adapt to this reality, artefacts of resilience like ordered lists and extensive spreadsheets outlining the next best journal, and the next best journal after that.

If we were to translate these stories back to musical notation we’d conclude that the real experience is anything but a linear staccato experience. Instead things overlap, clash, repeat, take a short or indeed very long time. But, of course, it wasn’t enough for me to hear these stories, I had to convey the image of entangled messy experience to the wider organisation.

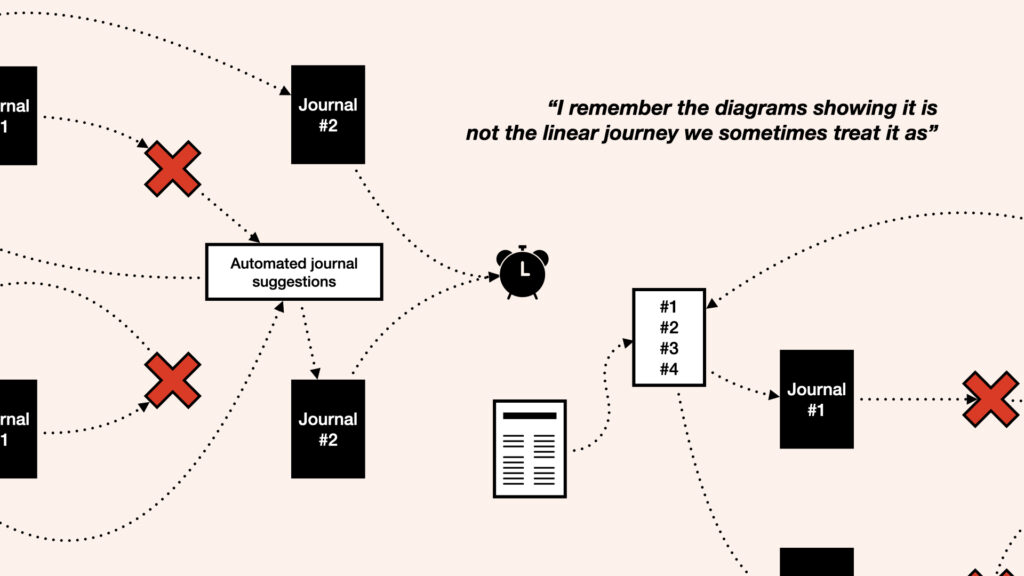

I had to tell them about the post doc in Europe who had just been rejected by the third journal he submitted to. They told him it was nicely written, but not appropriate for the journal. He thought that was “nice to hear.”

I had to tell them about the South American professor who is working his way through his journal shortlist. His university expects 2.5 publications in top journals, but his paper has been rejected twice already. He will submit again tomorrow, he said, “I’m confident it will get published, my morale is intact.”

And I had to tell them about the student in Asia, who is officially going in circles: after two rejections they are adding new research studies to the paper to make it – quote – “more novel” after which they’ll go back to the journal that rejected them first.

But would these stories stick with the stakeholders who I hoped would consider how these experiences are reflected in our roadmaps? Would they paint a vivid picture of the messiness? To challenge the oversimplification of the usual maps, I had to somehow visually convey the complexity of reality. I set out to overwhelm.

So with curvy lines and looping arrows I mapped out each individual story. A purposeful attempt at visual noise. A cacophony of iterations. These stories weren’t simple, I wasn’t going to summarise them in a simple way. Many of these lines represent how academics overcome setbacks: on a small scale setback to publish their work, on a larger scale setbacks to succeed in academia.

I wanted to convey that the North American post doc I spoke to was working on two papers at the same time, and that a bad experience with the first paper impacted her behaviour when she decided what to do with the second paper.

And I wanted to tell them about the European lecturer in social science, who explained that “in practice, [a journal’s word limit] is often the number one factor that decides if I’m able to submit to a journal or not”. Shortening her paper significantly would compromise her research: it was not an option.

Three months after presenting this clutter, a senior stakeholder interrupted a colleague who was describing a simple sequential experience. He said: “I remember the diagrams showing it is not the linear journey we sometimes treat it as”. I think the image stuck.

Summarising these narratives linearly masks the labour involved in scientific progress and career progression, and it hides the core competencies of the people involved: they have patience, willpower, humility, adaptability, and a lot of resilience.

So this is a call for mapping reality: creatively convey friction, delay, complexity, and confusion. Whatever you do, don’t simplify. Honour the mess.

With thanks to Jez Alder (Principal Designer at Elsevier) and Niels van Dantzig (Senior Product Manager at Elsevier) who made this project happen. Thank you Gigi Taylor (Indeed) and the EPIC team for curating and helping develop this Pecha Kucha.