What if sensors were installed in all toilets? And what if the data these sensors collect is presented publicly, on a website? To kickstart a debate on the potential implications of such technology a small team of people — including myself — created this illusion during an academic tech conference in 2014: we built a fake website and placed ‘quantified toilets’ signage in bathrooms throughout the conference centre. Some believed it to be real, others quickly concluded it was fake. Twitter was alight with responses. Within two hours the conference confirmed it was “a joke”, and all signage was removed.

The ‘thought experiment’ received extensive media coverage and academic outrage. The Quantified Toilets project was deemed unethical due to its use of deception — conference attendees were, after all, temporarily made to believe the technology was real. In the following months some of the team members involved were prevented from publishing their reflections on the response by the academic institutions they were affiliated with.

But while the academic world deemed the experiment too unethical to publish, real life has thrown caution to the wind: bathroom surveillance is now a reality. Startups have launched ‘toilet IoT sensors’ and promise to “make your toilet smart”. In Australia a plan was announced to analyse sewage in areas with high drug use.

As Zeynep Tufekci recently tweeted:

It is possible to stop academics from doing proof-of-concept studies. It won’t lessen the real-world applications, just mute the warnings.

How it all started

In 2014 I took part in a two-day hackathon in Toronto on ‘critical making‘, organised during CHI2014 — the largest human-computer interaction conference.

The brief was simple: spend two days thinking, discussing, and tinkering around the themes of sensing technology, privacy, and surveillance. Afterwards, present your findings at the main conference, for example by installing whatever you have built somewhere in the conference centre.

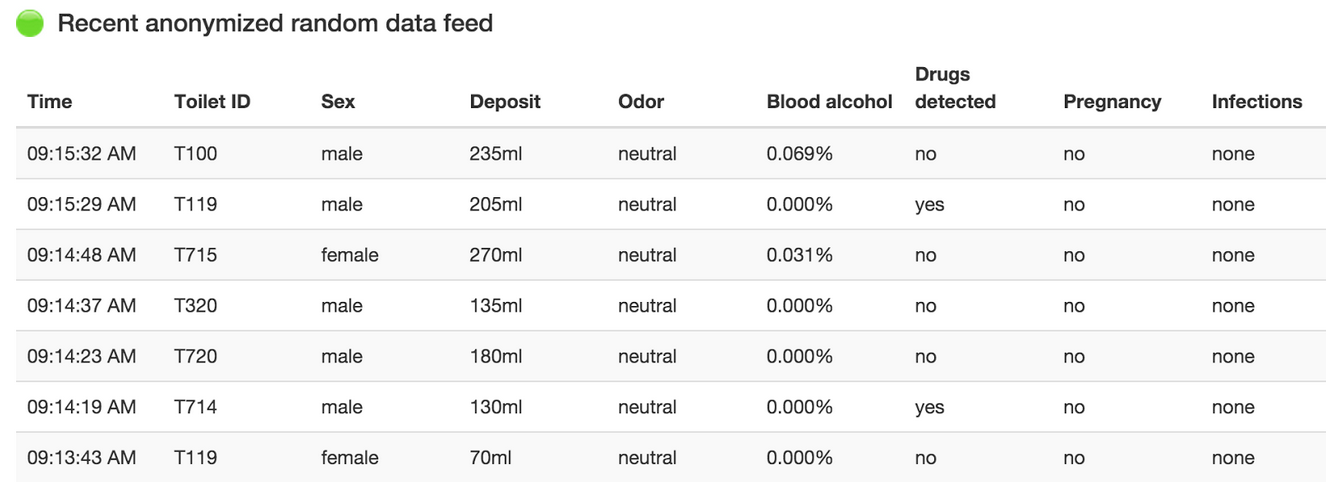

We formed groups, and had to decide on a topic. Sensing, surveillance, consent, ethics… Within minutes a choice was made: let’s spend our time on critically thinking about the most outrageous concept we can think of — sensors in toilets. And let’s take it one step further: let’s imagine a world in which sensors in toilets publish data straight onto a website, allowing anyone to see the size of the most recent deposit (‘225ml’), odour (‘sulphuric’), blood alcohol levels, whether any drugs have been detected, and whether or not the person in question is pregnant.

Let’s just pretend

Typically, hackathons involve at least some coding or soldering, but after a lengthy discussion we concluded we did not really need to build anything at all. Instead, we could just pretend. We created a narrative: we were a startup — Quantified Toilets — and had developed advanced toilet surveillance technology. We registered the quantifiedtoilets.com domain and spent time building a simple website and finessing suitable and convincing content (“Our groundbreaking software is able to catalog the data for a multifaceted health analysis not currently available through traditional means”).

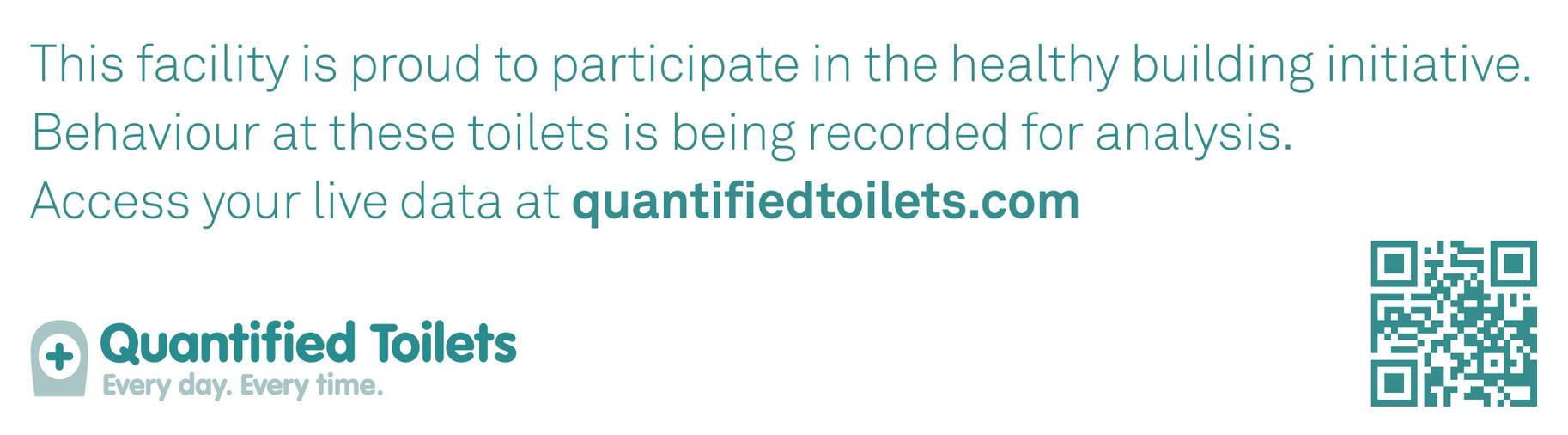

We also created stickers to inform anyone visiting a participating bathroom of the initiative, and to let them know where they could view their data:

Ready, set, go

Two days later, before the start of the conference’s keynote at 9 o’clock, we set out with a few dozen of these stickers and stuck them on the inside of the doors of several bathroom stalls throughout the conference centre.

It did not take long for the first tweet to appear, and soon many more followed. The conference organisers confirmed that Quantified Toilets was “a joke”, but by then the news had spread far beyond the conference. We started receiving media enquiries, and the Toronto city authorities got in touch to check if this technology had actually been installed. The project’s website was updated to confirm it concerned a ‘thought experiment’. A impromptu panel session was organised at the conference to discuss the project.

To say that the project kicked off a debate would be an understatement. Over the course of a week the Quantified Toilets website was visitors just under 25,000 times. The project was featured on Wired, Gizmodo, Mashable, The Washington Post, The Daily Dot, and several other publications. Some presented it as an amusing hoax, others wrote in-depth articles on the lessons that could be learnt from Quantified Toilets about the future of surveillance — such as Jennifer Golbeck in The Atlantic. Eventually, the project even made its way into a book.

Ethics

However, there was backlash too. A number of academics were not impressed by the way the Quantified Toilets project was carried out: the project had purposely deceived people — and even though this was temporary, it had still happened. Some of those involved in the project also received written warnings from their university’s internal review board — the people that decide whether work follows the university’s ethics guidelines — and were told the project had crossed a line. They were not allowed to publish articles on Quantified Toilets.

Honesty and informed consent are, rightfully, at the core of academic work. The main premise is that all research should have integrity, and as such all work is scrutinised by academic institutions, publishers, and through peer-review. Where a ‘design fiction’ project like Quantified Toilets fits within the strict ethical guidelines is less clear. As Bruce Sterling explains:

Design fictions are fakes of a theatrical sort, but they’re not wicked frauds or hoaxes intended to rob or fool people. A design fiction is a creative act that puts the viewer into a different conceptual space for a while. Then it lets him go. Design fiction has an audience, not victims.

By forbidding people to publish articles on the responses to this type of work academia closes a door on the opportunity for debate. Technology is developing at a fast pace, and the use of design fiction (or ‘speculative design’) may be the most appropriate way for researchers to study ecologically valid responses to new inventions.

In a world where a discussion on the use of alternative approaches to future tech research is impossible, academia will play catch-up with reality. It is a world in which we are all worse off, as the consequences of new technology will only be felt once it is already too late.